Every company claiming credit should check claims for repayment! – On the inadmissibility of so-called processing fees in loan agreements with companies.

/in Commercial law, Liability law, Nicht kategorisiertLEGAL+ NEWS

According to recent rulings by the Federal Court of Justice (judgments of 4 July 2017, case no. XI ZR 562/15 and case no. XI ZR 233/16), processing fees that have been customary for a long time are also inadmissible for loans to companies and thus corresponding agreements in loan agreements – even in the case of overdraft facilities – are invalid. Consequence:

The companies concerned may therefore be able to reclaim the fees paid from their banks within the applicable limitation periods. With the end of the year approaching and the impending statute of limitations for claims arising from 2015, the key findings of the BGH are recalled as follows:

The guiding principles

The guiding principles of the BGH are as follows:

1. the formal clause contained in loan documents of a credit institution for the conclusion of loan agreements with entrepreneurs

“Processing fee for conclusion of contract €10,000”

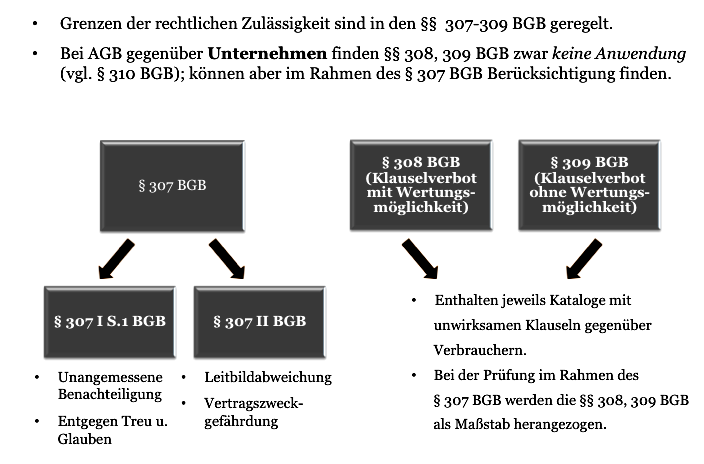

is subject to judicial review of content pursuant to Section 307 (3) sentence 1 BGB and is invalid pursuant to Section 307 (1) sentence 1, (2) no. 1 BGB.

2 The knowledge-dependent limitation period of Section 199 (1) BGB for claims for repayment due to ineffective formally agreed processing fees also began to run at the end of 2011 for loan agreements with entrepreneurs in accordance with Section 488 BGB (continuation of Sen.Urt. v. 28.10.2014 – XI ZR 348/13, BGHZ 203, 115 RdNr. 44 ff.).

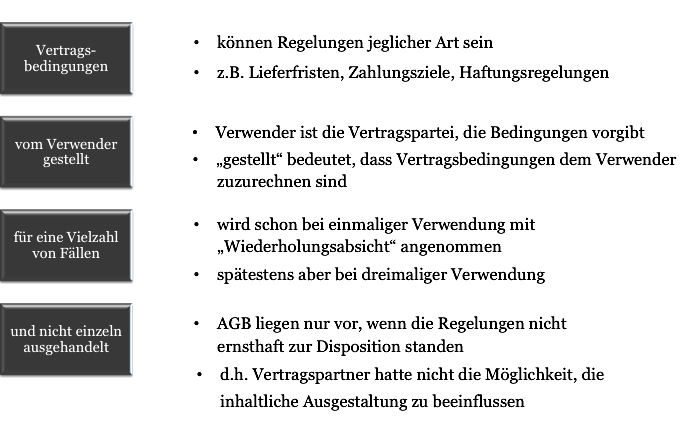

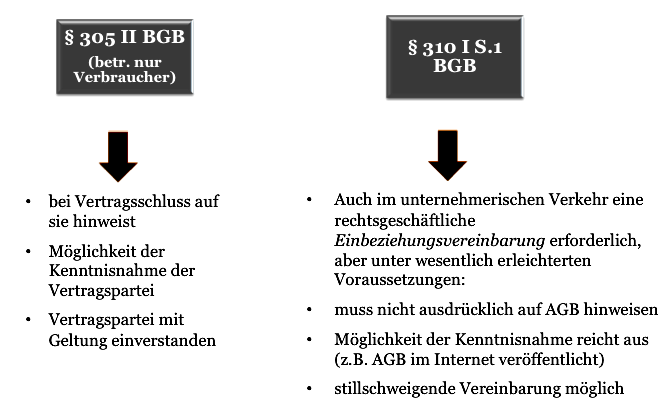

Processing fee = ancillary price agreement

In the proceedings decided by the BGH, the borrowers were each entrepreneurs within the meaning of Section 14 BGB. The loan agreements concluded with the respective banks contained standard form clauses according to which the borrower had to pay a “processing fee” or a“handling fee” irrespective of the term of the loan. The subject of the lawsuits is the repayment of this fee because, in the opinion of the plaintiffs, the clauses in question are invalid.

In its reasoning, the BGH clarified that the challenged clauses are so-called ancillary price agreements, which are subject to content control in accordance with Section 307 BGB.

Unreasonable disadvantage

The BGH considered these ancillary agreements to be an unreasonable disadvantage to the contractual partner.

Such term-independent processing fees are not compatible with the essential basic ideas of the statutory provision, which is why, in accordance with Section 307 (2) No. 1 BGB, an unreasonable disadvantage to the contractual partner can be assumed in case of doubt.

Tax advantages no justification

In the cases to be decided, the BGH was unable to identify any reasons for a deviation from this legal presumption. In particular, the reasonableness could not be justified by any resulting tax advantages for the company concerned. Only those advantages that were originally granted by the user of the clause (in this case the bank) could be taken into account, as was not the case in the decided cases. The Federal Court of Justice (BGH) stated in this regard – summarized by me:

“(…) It is recognized that a deviation from the dispositive statutory law which is disadvantageous to the contractual partner can be compensated for by granting other legal advantages (Sen.Urt. v. 23.4.1991 – XI ZR 128/90, BGHZ 114, 238, 242 f. and 246). However, the imbalance in the content of a clause that unilaterally favors the user can only be compensated for by advantages for its contractual partner that are granted to it by the user of the clause (see also Sen.Urt. v. 21.4.2015 – XI ZR 200/14, WM 2015, 1232 RdNr. 18). It is therefore irrelevant whether individual traders can succeed in passing on the financial disadvantages they suffer as a result of the challenged clause to their customers through over-obligatory efforts. (…)

For the same reason, the appropriateness of a term-independent processing fee cannot be justified by any resulting tax advantages on the part of the entrepreneurial borrower – combined with a lower contractual interest rate….

(2) Irrespective of this, an inappropriate disadvantage to customers due to fees agreed in general terms and conditions is not offset by a lower interest rate within the scope of the content review pursuant to Section 307 BGB simply because individual customers are able to immediately deduct a larger part of the processing fee incurred for tax purposes (…).

No justifiable commercial practice

Furthermore, it is also not apparent that such fees appear to be justified if reasonable consideration is given to the customs and practices applicable in commercial transactions (Section 310 (1) sentence 2 half-sentence 2 BGB). In any case, in the cases to be decided, the banks were unable to prove a corresponding commercial practice.

Finally: Entrepreneurs are also worthy of protection

According to the BGH, the protective purpose of Section 307 BGB, which is to limit the use of unilateral drafting power, also applies in favor of an informed and experienced entrepreneur. The fact that an entrepreneur can better estimate an overall burden resulting from various fee components is not suitable to prove the appropriateness of such clauses when used against entrepreneurs. The review of the content of general terms and conditions is generally intended to protect against clauses in which the dispositive statutory law aimed at a mutual balance of interests is overridden by the unilateral power of the user of the clause. The BGH was – in my opinion rightly – not able to recognize any indications that credit institutions could not claim such unilateral creative power vis-à-vis entrepreneurs. In my opinion, the BGH correctly stated:

“(…) There is also no indication that credit institutions could not claim such unilateral power to shape the contract in relation to entrepreneurs – unlike in relation to consumers – as the situational inferiority of entrepreneurs is generally lower than that of consumers. On the contrary, the economic situation of entrepreneurs, whose business success depends on the granting of a loan, may well show a higher degree of dependence on the credit institution than is the case with consumers who apply for a real estate loan for the purpose of building their own home or even just for a consumer loan (…).”

Conclusion:

Every entrepreneur who claims loans should check their loan agreements against the above case law and, if necessary, assert claims for repayment. In view of the impending statute of limitations for claims from 2015, haste is required.

LATEST ARTICLES

The court’s duty to provide information in civil proceedings

It is not uncommon for courts to simply remain silent until the first hearing date – in the worst case, years can pass until then. As a result, the parties do not know where they stand for a long time and eagerly await the hearing date, from which they hope to finally learn the court’s point of view. It is often only during the court hearing that judges then issue so-called judicial instructions in accordance with Section 139 (2) and (3) ZPO. This procedure is unlawful!

Reference to USB stick in the application

Our latest article analyzes the BGH ruling of 14.07.2022, which for the first time allows reference to a USB stick in the claim. Find out how this ruling expands the scope of digitalization in civil proceedings and what consequences it has for practice.

Action dismissed as “currently unfounded”

Disputes under construction law in particular often concern the due date of remuneration claims, e.g. because acceptance as a prerequisite for payment is questionable. In these cases, it is not uncommon for judgments to be handed down in which a claim is dismissed “as currently unfounded”.

The BGH recently stated in detail that in such cases the res judicata effect of the dismissing judgment also includes the grounds for the judgment, insofar as the other – i.e. the currently not missing – claim requirements have been positively established or affirmed.

CONTACT

+49 (40) 57199 74 80

+49 (170) 1203 74 0

Neuer Wall 61 D-20354 Hamburg

kontakt@legal-plus.eu

Benefit from my active network!

I look forward to our networking.